Gregory of Tours' account of the marriage of Clovis and Clotilda portrayed the Burgundian King Gundobad (and Clotilda's uncle) in an unflattering light. Yet, the truth may have been different than that put forth by the Merovingian propagandist and the debate regarding the credibility of Gregory's account has encompassed nearly as many years as did the duration of the short-lived second Burgundian Kingdom in Gaul!

Most historians from the time of Gibbon to the turn of the 20th century seem to have taken Gregory's stories at face value. However, some historians--like Godefroid Kurth, who was an early skeptic (relatively speaking) of the Gregory account--have questioned some of Gregory's tales. Kurth examined Gregory’s own sources and concluded that Gregory relied too much on legend, which he uncritically used to fill in gaps in his historical record. Another, later, historian--I.N. Wood--remarked that:

the account of fifth-century Gaul offered by Gregory in his Histories is intended, on the one hand, to denigrate the Arian Goths and Burgundians, and, on the other, to elevate the Franks and their king, the Catholic convert, Clovis.

J.M. Wallace-Hadrill unequivocally stated that Gregory’s hero is Clovis, and Gregory placed Clovis’ conversion too early to make it appear as if all of Clovis’ great deeds were done as a Catholic. (Wallace-Hadrill’s chapter, “The Work of Gregory of Tours in the Light of Modern Research,” in

The Long-Haired Kings, is informative on the subject Gregory’s work, point of view and motivation). Ian Wood also urges us to take Gregory with a grain of salt:

Gregory’s account of Clovis seems to be more concerned to create the image of a catholic king against whom his successors could be assessed, than with any desire to provide an accurate account of the reign. In order to understand Clovis within the context of the late fifth and early sixth centuries it is necessary to emphasize the contemporary evidence, and to treat Gregory, as far as possible, as a secondary source.

Despite these warnings, many have continued to uncritically accept Gregory's account of Clotilda and the events surrounding her while she lived in Burgundy.

That Clovis probably married her in the early 490’s and that she was the niece of King Gundobad is accepted, but that is about it. Some historians have contended that the story, or legend, of Gundobad’s murder of Chilperic II and Clotilda’s subsequent desire for revenge grew up about a generation after the marriage of Clovis and Clotilda.

Skeptics of the widespread acceptance if Gregory's tale as historical fact have relied on a textual criticism of both Gregory and the Fredegarius account as well as other sources that mention Clotilda, especially the

Saint’s Lives. They have contended, to quote Kurth, that the story of Gundobad murdering Chilperic II threw “a shadow over the character of Clotilda [ie; her later supposed desire for revenge upon her uncle, Gundobad], and a still darker shadow over the character of King Gundobad” and maintained that the “the very basis of [the story] is entirely fictitious.”

Some skeptics have held that Clotilda had no reason to avenge her father’s death by Gundobad because Gundobad didn’t commit the murders. They cited as proof a letter written by Bishop Avitus of Vienne to console Gundobad on the death of a daughter. Within this letter, Avitus wrote that, “[i]n the past, with ineffable tender-heartedness, you mourned the deaths of your brothers.” Accordingly, the brother mentioned was not Godegisil who later fought Gundobad and died, so it must have referred to Chilperic II. Another alternative may have been that the unnamed brother was the mysterious Godomar, who was barely mentioned in the sources and is but a name listed along with Gundobad and his Burgundian brothers.

Thus, skeptics contend, Avitus’ letter seems to absolve Gundobad of the murder of Chilperic II. Herwig Wolfram noted that, “It is likely that both Godomar and Chilperic II—the father of Clotild[a], the future wife of Clovis—died natural deaths around 490.” J.B. Bury also expressed doubts that Gundobad murdered his brother and explained that Gregory was engaged in a bit of medieval "retcon" (my term, not Prof. Bury's!).

Bury says that the legend of a vengeful Clotilda “originated sometime after the great war of A.D. 523 between the Burgundians and the Franks.” This is the year that Gundobad's son and heir Sigismund and his family perished at the hands of Clovis' and Clotilda' sons by being thrown down a well. As such, to explain the reason that two closely allied families would go to war, a story was invented by, as Bury put it, "popular imagination" to help explain why saintly Clotilda would allow her sons to kill their kinsmen. So the story of old wrongs was created and the connection is made by portraying the old wrong to have been nearly identical to the form of revenge perpetrated.

Because King Sigismund and his wife were killed and thrown in a well, the legend grew that the same happened to Chilperic. Because Sigismund’s two sons were killed, then two sons of Chilperic--sons who may have never actually existed--were said to have been killed by Gundobad. Bury contended that "we can thus safely conclude that the true Gundobad was not the sanguinary tyrant of later tradition, nor was Clotilda the bearer of tragedy and doom to the Burgundian house as she appears in the story."

Justine Davis Randers-Pehrson has explained some of the historiographical problems with Gregory's story of Clovis, in general. First is the chronological problem, “which is wellnigh hopeless.” It has been the subject of scholarly debate for decades. “What confidence can be placed in judgments that sometimes must be based on the tense of a verb in a manuscript corrupted by copyists whose knowledge of Latin was admittedly faulty?” The second problem is on the primary source, Gregory of Tours. He “was a honest man, but he was possessed with a burning desire to prove that Clovis, from a very early time in his extraordinary career, had been the champion of true Christianity.” She also noted that most agree Gregory placed Clovis’s conversion too early so that all of his campaigns would be deemed victories for the Church. The third problem is the anachronistic belief that Clovis sought to create a French nation. “In reality," Randers-Pehrson writes, "if we read closely, he was a greedy opportunist who seized upon whatever chances arose in the flux of any given critical situation.” The first two problems seem viable while the last may be a bit too cynical for most.

While Kurth relies heavily on Saints Lives to poke holes in Gregory's accounts, others are wary. In

Forgetful of Their Sex, author Jane Tibbetts Schulenburg warned that, while hagiography often provided the only source of information for medieval women, it is important to note that most hagiographers were less historians than saint propagandists. This does not necessarily exclude Saints Lives as valuable historical sources, she continued, but historians must be aware of the motivation of the hagiographer. Schulenburg is far more accepting of Gregory's account, which she used to conclude that Clotilda was a woman who was active in determining her own destiny:

Considering that Gundobad had killed her parents and exiled her sister, and continued to espouse Arianism, Clotilda was no doubt anxious to escape from his court and to start a new life.

Ian Wood and J.M. Wallace-Hadrill were also wary of the accounts in the Saints Lives and, despite their misgivings about Gregory, were willing to accept much of his tale concerning Clotilda and her vengeance. In his description of Clotilda urging her sons to attack Gundobad’s as part of a “blood feud,” Wallace-Hadrill notes that, “Some historians look upon the story as essentially a myth. I do not know why.”

For his part, Kurth believed that both Fredegarus and the monk of St Denis, who wrote the

Liber Historiae, were even less critical of their sources than Gregory. Kurth also offered a defense of the hagiographers when he wrote:

[O]n this occasion at least hagiography can defend the legitimacy of its traditions in the name of science, while on the other hand we have the amusing spectacle of rationalistic learning, engaged in angry argument against the conclusions of the critical methods. Can it be true that in the estimation of certain historians the legends which glorify the saints are the only ones to be struck out, while those that calumniate them are to be preserved with pious care?

Regardless of this lively ongoing debate, the political factors that influenced the marriage are obvious. There appear to have been two factions in the kingdom of Burgundy; one that favored an alliance with the Franks, led by Godegisel, and another that mistrusted such an alliance, led by Gundobad. Clotilda had been living at Geneva*, the capital of her uncle Godegisel, who made a secret pact with Clovis. Thus, that Clotilda was Catholic was known to Clovis beforehand and was probably considered to be a desirable condition.

“Pious intrigue” was probably partly influential in matching a Catholic princess with the king of the pagan Franks. Since the Burgundians were known Arians, as were all of the other barbarian tribes, was it a coincidence that Clovis chose a Catholic Burgundian princess from this particular tribe?

However, though the Burgundians were Arian, they also seemed more tolerant of their Catholic subjects than the Vandals and Visigoths, and some of Gundobad’s closest advisors, such as Patiens and Avitus, were Catholic bishops. Though he may have not yet been Christian himself, it is probable that Clovis realized the political benefits of having a Catholic wife, especially one related to, at the time, a strong Arian kingdom that was also sympathetic to Catholics. The Burgundians also realized the importance of political marriages, as when Gundobad married his son to Theoderic’s daughter. For Clovis though, a marriage to Clotilda was more important for the ties it would strengthen to the dominant Roman Catholic Church than with those of the Burgundian kingdom.

Whether Gregory’s or Fredegarius’s accounts of Clotilda’s flight from the Burgundian kingdom to meet her betrothed are believable or not, what has been generally accepted is that the marriage was arranged at Chalon-sur-Saone and that Clovis met her at Villery, south of Troyes, and accompanied her to Soissons for the wedding. As Kurth explained, a poem written describing the ceremony replaced the historical facts as the historical record.

In this way legend at an early date took the place of historical fact, and, during many centuries, all that was best known of the life of Clotilda was that which never really occurred.

* Though, as I've already

noted, Gregory's story of Clotilda's engagement and betrothal to Clovis implies Clotilda is at Gundobad's court (which is in Lyons), not Geneva.

UP NEXT: Clotilda, Clovis and the Conversion

SOURCES:

Avitus of Vienne, Shanzer and Wood.

Gregory of Tours,

The History of the Franks.

Fredegarius,

Chronicle of Fredegar.

Godefroid Kurth,

Saint Clotilda.

I.N. Wood, “Continuity or calamity?: the constraints of literary models,” in

Fifth-century Gaul: a crisis of identity?, ed. Drinkwater and Elton.

J.M. Wallace-Hadrill,

The Long-Haired Kings.

Ian Wood,

The Merovingian Kingdoms.Kurth, “St. Clotilda,” in

Catholic Encyclopedia, 1908 ed.

Justine Davis Randers-Pehrson,

Barbarians and Romans.

J.B. Bury,

Invasion of Europe.Jane Tibbetts Schulenburg,

Forgetful of Their Sex: Female Sanctity and Society ca. 500-1100.

Herwig Wolfram,

Germanic Peoples.

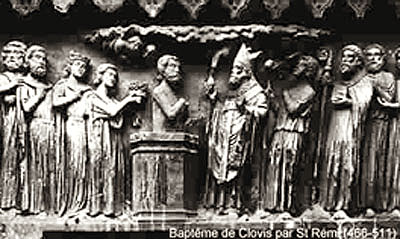

laid the groundwork for his conversion. Championing Clotilda's primacy as the prime mover behind Clovis' conversion, Jane Tibbetts Schulenburg (Forgetful of Their Sex) writes, it’s “the ‘Christ of Clotilda’ whom Clovis invokes” and “neither St. [Remigius] nor other members of the official church hierarchy were similarly awarded this type of prominence.” In contrast, Wallace-Hadrill asserted that while Clovis showed goodwill to the Catholic bishops by his marriage to Clotilda, the acute act of his marriage to Clotilda did not prompt his conversion, despite the efforts of his wife and Bishop Remigius. However,Wallace-Hadrill was willing to concede that the groundwork laid by Clotilda and Remigius may have played a key part:

laid the groundwork for his conversion. Championing Clotilda's primacy as the prime mover behind Clovis' conversion, Jane Tibbetts Schulenburg (Forgetful of Their Sex) writes, it’s “the ‘Christ of Clotilda’ whom Clovis invokes” and “neither St. [Remigius] nor other members of the official church hierarchy were similarly awarded this type of prominence.” In contrast, Wallace-Hadrill asserted that while Clovis showed goodwill to the Catholic bishops by his marriage to Clotilda, the acute act of his marriage to Clotilda did not prompt his conversion, despite the efforts of his wife and Bishop Remigius. However,Wallace-Hadrill was willing to concede that the groundwork laid by Clotilda and Remigius may have played a key part: